Cubital tunnel syndrome

What is cubital tunnel syndrome?

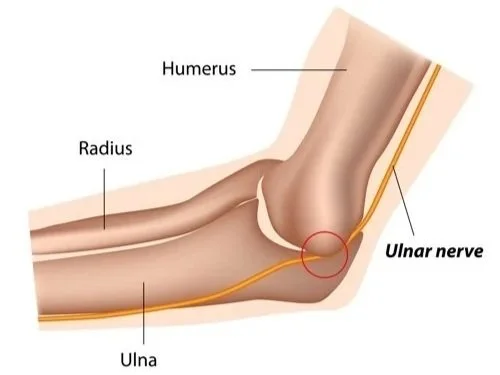

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a condition that occurs when one of the main nerves of the arm is compressed as it travels behind the inside part of the elbow. It is also known as ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. It causes numbness and tingling in the pinky and ring fingers and can lead to muscle weakness or damage in your hand in severe cases if not treated.

The cubital tunnel refers to the narrow passageway that runs under a bump of bone at the inside of your elbow (known as the medial epicondyle). This tunnel houses the ulnar nerve, which is responsible for giving feeling to your pinky finger and half of your ring finger, as well as controlling the hand muscles that help with fine movements, and some of the forearm muscles responsible for a strong grip. Cubital tunnel syndrome occurs when the ulnar nerve is compressed either because the cubital tunnel is reduced in size, or you stretch the nerve by bending your elbow and reduce its blood supply. Many people have temporarily felt the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome when they have ‘hit their funny bone’.

The factors that increase your risk for developing cubital tunnel syndrome include:

Prior fracture or dislocation of the elbow

Arthritis of the elbow

Elbow joint swelling or elbow joint cysts

Repetitive activities that require the elbow to be bent for long periods of time

How do I know if I have cubital tunnel syndrome?

In most cases, the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome are felt in the hand, despite the location of the disease being in your elbow. Generally the symptoms develop slowly, however as the condition worsens one or more of the following symptoms may persist for long periods of time.

Numbness/tingling or the feeling of ‘falling asleep’ in the pinky and ring fingers. This is more often felt when the elbow is bent.

Shock-like sensations felt through the pinky and ring fingers.

Weakening of your grip and difficulty with finger coordination (eg. typing or playing an instrument).

In severe cases, muscle wasting in the hand may be visible.

Waking at night with any of the above symptoms is quite common.

How Ben can help?

Diagnosing cubital tunnel syndrome

Ben will first chat to you about your general health, medical history and what symptoms you are feeling. He will then use two methods to diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome:

Physical Examination: Ben will examine your elbow and hand and perform several tests to ascertain whether there is tingling, numbness and/or weakness. These tests include tapping over the nerve at the ‘funny bone’; checking whether the ulnar nerve slides out of its normal position when the elbow is bent; and checking for weakness and/or wasting of muscles in your hand and fingers. Ben may also do a neck exam, as similar symptoms may be observed with pinched nerves in the neck.

Imaging tests: While physical examinations are often enough to diagnose cubital tunnel syndrome, Ben may order further tests in certain circumstances. Nerve conduction studies (NCS) measure how well your nerves are working and help to diagnose how severe the ulnar nerve is compressed and whether the pinched nerve is at the elbow, wrist or neck. NCS can also help Ben ascertain whether there is muscle damage associated with the compression. An X-ray provides images of bones and may be ordered to rule out other causes of your symptoms, like bone spurs or arthritis.

Treating cubital tunnel syndrome

Non-surgical treatment

Non-surgical treatment is generally offered first, unless there is muscle wasting observed in the hand.

Ben may recommend bracing or splinting the elbow overnight to limit bending while you sleep. This reduces pressure on the nerve in the cubital tunnel and can therefore reduce the symptoms.

If your symptoms are brought on by particular activities you do recreationally or at work, Ben may recommend modifying how you perform the task/s to limit the amount of time your elbow is flexed.

In some cases, Ben may suggest medication to help treat cubital tunnel syndrome. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen can help to relieve inflammation, however usually these just provide temporary relief of symptoms. Note that steroid injections (cortisone) are generally not offered for cubital tunnel syndrome because there is a risk of damage to the nerve.

In conjunction with these non-surgical treatment options, Ben will usually refer you to a hand therapist who will develop an exercise plan with you to help the ulnar nerve move more freely through the cubital tunnel, thus reducing symptoms.

Surgical treatment

Ben will usually recommend surgery if the non-surgical treatment options fail to provide relief. The goal of surgery is to relieve pressure on your ulnar nerve, however there are two main procedure options that achieve this result depending on the severity of the compression.

A ‘cubital tunnel release’ is generally offered if the compression is mild or moderate and the nerve does not slide out from behind the bony ridge of the medial epicondyle. In this procedure, Ben will cut and divide the ligament that forms the roof of the cubital tunnel, which increases the size of the passageway.

A ‘ulnar nerve transposition’ procedure moves the nerve from its place behind the medial epicondyle or a new location in front of it. This stops the nerve from getting caught and stretching every time the elbow is bent.

In both cases, the procedures are usually done on an outpatient basis, where you will be given general anaesthesia, but will be able to go home the same day.

You will be asked move your elbow straight away to avoid any scarring of the nerve, but heavy lifting should be avoided for several weeks after surgery.

In some cases you will need to wear a splint for several weeks after surgery. Hand therapy is usually also recommended to maximise your recovery and ensure optimal strength is regained.

Patients usually notice improvement in their symptoms within the first 1-2 weeks, particularly overnight, however, it can take up to one year for patients to make a complete recovery.

-

Ben operates at multiple hospitals across Melbourne’s bayside and peninsula region, including:

Linacre Private Hospital, Hampton

Peninsula Private Hospital, Langwarrin

The Bays Private Hospital, Mornington

He can discuss your preferences in person during your consultation.

-

Ben will see you for a post-operative appointment usually 2 weeks after your surgery. During this appointment he will asses your wound and check that healing and mobility is progressing as expected. There will be no cost for this appointment.

As well as this, Ben will usually refer you to a physiotherapist, who focuses on rehabilitation after an injury, and will work with you to improve function of the affected area.

-

You can usually start driving again 4-6 weeks after the operation. However, every surgery is different, so Ben will provide individualised advice as part of the initial consultation.